OFB columnist Dennis E. Powell has been doing critically acclaimed, widely influential work on the space program for decades, including three significant pieces on the Challenger disaster that came nearly two decade’s before Columbia’s final flight. Powell’s work on the Challenger disaster for TROPIC, the magazine of the The Miami Herald, earned him a Pulitzer nomination and can be found at the end of this week’s story.

Twenty year ago this morning I was having coffee when I remembered that the space shuttle was landing, so I turned on the television to watch it.

Everything seemed yawningly normal. But then I was interrupted mid-yawn — a very unpleasant sensation, though not as bad as a stifled sneeze — when the commander and pilot of the shuttle failed to respond to calls from the flight controller.

There’s always a blackout during re-entry during the period when ionized air, impenetrable to radio signals, makes communication impossible. It’s a well known phenomenon and generally no cause for concern. Not this time.

The returning shuttle was the Columbia, the oldest in the fleet. STS-1, the first space shuttle flight, was Columbia. In the early days, when it had a crew of two, it even had ejection seats, not that they’d be of any use in a re-entry problem. They’d gotten yanked when the crew got bigger. It’s impolite to wave goodbye to the passengers as you jump out to save your own skin, and there was no way to put a whole bunch of ejection seats in a space shuttle.

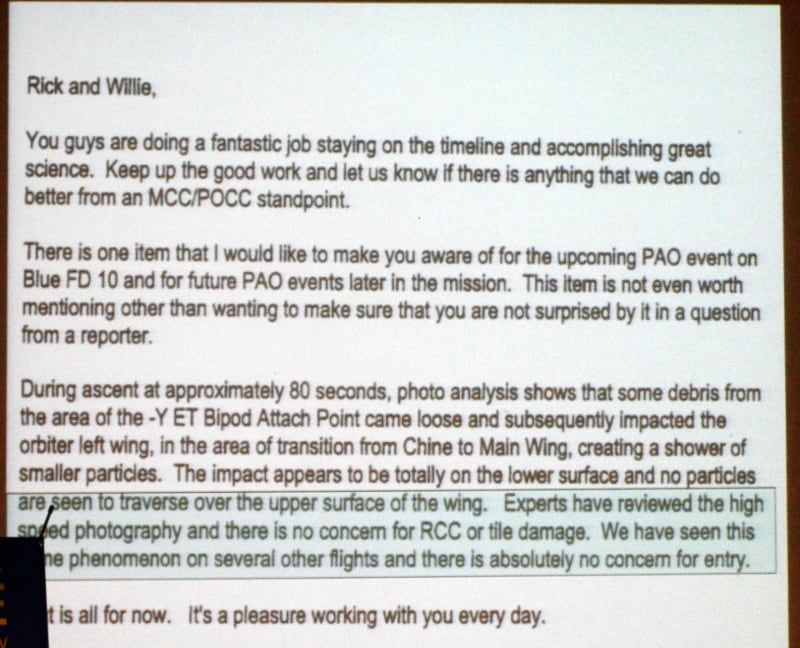

The current flight, STS-107 with a crew of seven, had seemed a little worrisome from the beginning. Hunks of foam insulation that covered the big orange external fuel tank had broken loose at launch, and pieces had hit the incredibly delicate tiles of the Thermal Protection System — the system designed to prevent shuttles from burning up on re-entry.

Engineers were concerned. Punch a hole in the TPS, do nothing about it, and you can expect to see a shuttle lost on re-entry. Which is exactly what happened this time.

The engineers started to study the problem, to try to figure out whether there had been damage to the tiles and, if there had been, what to do about it. While the details remain a little fuzzy, senior NASA Flight Director Wayne Hale and others initiated back-channel communication between themselves and folks at the Department of Defense, which had and has some pretty amazing satellites. You’ve seen the pictures in which a satellite image makes it possible to read a license plate on a car on Earth. Turn one of those sideways and you could look at the underside of the shuttle and assess the damage. This was planned — and then NASA called it off. Some Boeing engineers hired to say so had told NASA there was nothing to worry about.

”. . . I don't think we need to pursue this,” Mission Manager Linda Ham remembered saying. She recounted the event in a CBS interview months later. No one had appropriately approached her about getting satellite pictures taken.

Why was nothing done? Ham again remembered what she told her colleagues: “Really, I don’t think there is much we can do. It’s not really a factor during the flight because there isn’t much we can do about it.” She didn’t think there was any damage, so NASA would assume there was none and that was that. (Consider how Apollo 13 would have turned out if NASA had pretended that there was no problem. Instead, the engineers went to work, did the impossible, and brought the crew safely home. This time, led by Ham, NASA didn’t even try. If I sound angry 20 years later, it’s because I am. Still.) Wayne Hale was later promoted to Space Shuttle Program Manager. Ham was “promoted” to a job out west someplace involving the storage of hydrogen for use in renewable energy projects.

The foam had punched a hole in the leading edge of Columbia’s left wing. The hot gases the tiles were supposed to repel got into the wing. In a matter of seconds, the shuttle lost control and broke to pieces. The seven astronauts aboard were killed then or not long thereafter.

On the ground at NASA 20 years ago this morning there was confusion. When there was no word from the shuttle minutes after communication should have been established, everyone knew they had lost the second shuttle — now half of the original fleet had been destroyed. But everyone continued to read their lines, making plaintive radio calls that went unanswered. Then came word that there was a lot of stuff burning up in the sky over Texas. Pieces of the space shuttle and the astronauts.

I headed to the computer and got in touch with people who knew what was going on, the engineers. They had followed which sensors in the left wing had gone offline and the order in which they had failed. Of surprising importance was the tire pressure rise in the left landing gear, which suggested that it was getting mighty hot. The engineers were able even to speculate which TPS tiles were involved. It was breathtaking, particularly in light of NASA’s official where-oh-where-is-our-space-shuttle attitude. (The big map on the screen showed not where the shuttle was but where it would have been if it hadn’t been ripped to pieces.)

I phoned a friend at the Voice of America’s newsroom and told him what I was learning. He put me on the air. I was unprepared and was still getting information, so I probably sounded like a gibbering idiot, but what I said turned out to be accurate.

The country’s reaction was, um, subdued. The space shuttle wasn’t really that interesting anymore. We’d seen this show before, and the destruction of the Challenger in 1986 had been far better television anyway, with its own horror stories. And I’d written years earlier how engineers didn’t think that the shuttle was safe to fly, even after post-Challenger improvements. A leading vulnerability, they said, was the Thermal Protection System. So I don’t think anyone was much surprised. I wasn’t, and I’m not an engineer. The loss of Columbia was just NASA being post-Apollo NASA: Not a group of dedicated people doing great things but just another government agency grubbing for money and influence while delivering as little as possible

It is notable that NASA has killed astronauts during a single calendar week: the Apollo 204 fire on the pad on January 27, 1967, the Challenger on January 28, 1986, and, now, Columbia on February 1, 2003.

The shuttle went on to get retired, mercifully, in 2011. After having flown to the moon and back, NASA was reduced (but not its budget) to hitch-hiking to the useless International Space Station, which we built, aboard Russian rockets. One of our greatest triumphs, the manned space program, had become one of our greatest shames.

So I didn’t think much more about the Columbia disgrace. Not, anyway, until the summer of 2015, when the NASA-sponsored International Space University came to Ohio University in Athens and I covered it. On the night of June 30, several of those involved in both the ISU and in the final Columbia flight talked to the program’s participants, entitling their presentation, “The Human Side of the Columbia Disaster.”

John Connolly, the NASA engineer who headed the ISU, put the agency’s complacency in blunt terms: “It’s like you and your car. You think you know how far you can go when the needle is on empty. But one day it will get you.” Doug Hamilton, a NASA flight surgeon at the time of the disaster, spoke obliquely but sharply about Ham’s decision to avoid even investigating to see if there was a problem. “That’s still a touchy subject among flight controllers,” he said.

“The flight controllers were all very professional, but the scientists, who had just lost friends they had had over for dinner and worked with, they hadn’t signed on for this,” said Hamilton. The presentation included carefully recovered and pieced together recordings of shuttle-Earth calls between the astronauts and their families. These guys and their coworkers cared. NASA, if evidence matters, didn’t.

The official line was that it wouldn’t have mattered if NASA had known about the damage because nothing could have been done, but nobody believed it. NASA engineers — again, look at Apollo 13 — can do miracles given the opportunity. To this day they’ll tell you they would rather have tried and failed than have had their hands tied by NASA bureaucrats, as happened. A personal friend, a NASA safety engineer who was a suicide before the Columbia disaster, once rewrote software in real time, catching a bug that saved the first unmanned flight of the lunar rover around the moon. There are scores of similar saves, almost all of them not widely known. If only they had been given a chance this time . . . (It was reported later that some of them had begun plans to get the shuttle Atlantis ready for a rescue flight. Oh, but that would have screwed up NASA’s schedule.)

A review board was set up after the Columbia got destroyed. It issued a very long report. The report was not complimentary to NASA’s decision makers. “We are convinced that the management practices overseeing the Space Shuttle Program were as much a cause of the accident as the foam that struck the left wing,” the board announced. Said the report: “Perhaps most striking is the fact that management including shuttle program, Mission Management Team, Mission Evaluation Room, and Flight Director and Mission Control displayed no interest in understanding a problem and its implications. Because managers failed to avail themselves of the wide range of expertise and opinion necessary to achieve the best answer to the debris strike question ‘Was this a safety-of-flight concern?’ some space shuttle program managers failed to fulfill the implicit contract to do whatever is possible to ensure the safety of the crew. In fact, their management techniques unknowingly imposed barriers that kept at bay both engineering concerns and dissenting views . . .” (I think there was some debate over the use of the word “unknowingly.” I know I disagree with the use of the word “accident.”))

It laid out eight occasions after launch that action by NASA mission managers could have illuminated the problem and possibly saved at least the crew if not the shuttle itself. It pointed to William Readdy having turned down the offer from the Department of Defense to make images of the wounded shuttle as one of them. Mission Manager Linda Ham’s refusal to consider calls for a damage inspection of the shuttle was another.

Twelve years later, some of those who were left literally to pick up the pieces were still sorrowful, but philosophical as well.

“[Shuttle Commander] Rick Husband was a very religious man,” said Hamilton to the ISU students. “I’m sure that when he saw that the RCS [the system that uses small rockets to stabilize the shuttle] was saturated, he knew they were dead. And I’m sure he got on the intercom and told the others it was time for them to make peace with their maker.”

In February 2003, 22,000 people searched parts of east Texas and Louisiana — Connolly and Hamilton were among them — and ultimately recovered 38 percent of the shuttle and some human remains.

NASA said the crew died very quickly, but NASA has said that kind of thing a lot.

Dennis E. Powell is crackpot-at-large at Open for Business. Powell was a reporter in New York and elsewhere before moving to Ohio, where he has (mostly) recovered. You can reach him at dep@drippingwithirony.com.

You need to be logged in if you wish to comment on this article. Sign in or sign up here.

Start the Conversation